What If My Child Has Depression?

Posted in: Parenting Concerns, Teenagers

Topics: Depression, Mental Illness + Psychiatric Disorders

What is child depression, and when should you worry about it in your child or teen? See more, below.

Este artículo está disponible en español.

“Depression” is a funny term. Like lots of diagnoses in psychiatry, the word “depression” has both common and specific uses. Kids might complain of “feeling depressed” after a break-up, or not making the school team, but they tend to snap out of whatever funk they’re in relatively quickly. In these instances, they are simply using a common word that happens also to have medical connotations. It would be like a kid with a nasty cough saying he has “bronchospasms.” The difference, of course, is that most kids don’t say words like “bronchospasms.”

This confuses the issues a good deal when you’re dealing with the medical variety of depression. And depression is a serious, albeit extremely treatable, medical diagnosis. Depressed kids stand to lose a good deal of developmental growth, are at risk for problems like substance abuse and trauma, and may even be in mortal danger from suicide. Being vigilant about depression is a good idea, but how to do this isn’t always so clear.

Consider Julia.

Julia is 16 years old, just got her driver’s license, and drives her father’s pickup truck. The pickup also comes in handy for carting around the equipment for her band, an indie style punk group that she and three of her friends have formed. Julia’s a cool kid; she eschews the bass guitar for the old-fashioned stand-up bass, and she wears an old hat that she bought last year at a thrift shop. Her band is actually getting pretty good, and they had a major breakthrough when they made it to the semi-finals in a local battle of the bands at her school last fall.

But now her friends and her parents are worried. She’s cancelled the last three practices over the course of a few months. Her grades are falling, and all she does is sleep. She’s adamant that she isn’t using any drugs; she just doesn’t care about anything, and she wants everyone, especially her parents, to leave her alone. Last week, she posted a picture of nothing but black paint under a “self portrait” heading on her Facebook page. When her friends commented on her site, she refused to answer. This prompted a call from one of her friends to Julia’s parents, and her parents, glad to have an excuse other than their own worry, brought her to her pediatrician.

The pediatrician spent time with the parents and Julia together, and then with Julia alone. She learned that Julia’s paternal grandfather died by suicide. She also learned that Julia has felt pretty bad for the last month, and can’t detect a time when Julia seemed to be unusually energetic. She therefore concluded that Julia has depression.

“Of course she’s depressed,” her mother says. “Just look at her.”

What Is Depression?

Depression is a syndrome characterized by a persistently sad or sometimes irritable mood. In making the diagnosis, clinicians often refer to the neurovegetative symptoms of depression. These include poor sleep, decreased interest, low energy, guilty feelings and changes in appetite. In addition, depressed individuals may hold their bodies differently, sometimes barely moving, and other times, fidgeting excessively. Suicidal thoughts and behavior are the most alarming of these signs, although one need not be suicidal to be depressed. In general, an individual needs to experience a depressed mood as well as five neurovegetative symptoms to be considered clinically depressed (according to the current definitions). It is important to remember that some of these definitions may change with the new diagnostic categories of the DSM-V; however, if anyone suffers severely from even one of the symptoms, it’s good to keep in mind that clinical intervention will be helpful.

Data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) suggest that nearly 4% of children ages 3-17 have ever suffered from depression. Another study indicates a 37% increase of major depressive episodes reported by adolescents ages 12-20 — up from 8.7% in 2005 to 11.5% in 2014. Approximately 15–20% of adolescents will experience depression during their teen years.

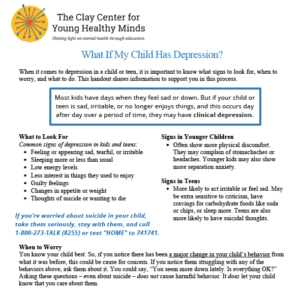

What Does Depression Look Like?

Because kids change so much as they grow, depression in young people can look different than that in adults, and can even look different among children of varying ages. Add to this what is perhaps the more obvious dilemma: depressed teens often have atypical depressive symptoms. Instead of feeling sad, they may feel irritable. Instead of losing their appetites, they may crave more carbohydrate-rich foods. Instead of having difficulty sleeping, they may sleep all the time. They also may manifest their irritability frequently in the form of extreme sensitivity to criticism.

So, the tired, sensitive, junk-food-eating kid could be depressed—or more likely just a typical teen. This is why the issue of mood disorders among adolescents can be so confusing. Good clinicians will spend a fair amount of time teasing apart normal developmental challenges from clinical depression, and information such as family genetic history and loss of interest in previously-enjoyed activities (such as playing guitar, for example) are important clues.

Despite the different ways that depression can look in young people, there are some generalizations:

- Depressed younger children typically voice more physical complaints than do their adolescent counterparts.

- Headaches or stomachaches are common among depressed pre-adolescents, though these are very general symptoms.

- Younger children will often exhibit increased separation anxiety.

- Nearing adolescence, those who suffer from depression start to resemble adults with the same illness, with the exception that there are more of the atypical symptoms noted above.

- Teens are more likely to feel seriously suicidal.

To further confuse matters, studies fairly consistently show that parents are often not aware of their teen’s depressed feelings; kids will go to great lengths as a function of social pressure to seem OK. This means that a knowledgeable individual will ask directly about the experience of depression in an adolescent.

The ratio of boys to girls with depression also shifts as kids get older. Pre-adolescents have about equal rates among boys and girls, but during adolescence, girls with depression outnumber boys by approximately 2 to 1, and this ratio persists into adulthood. Most clinicians and researchers feel that biological and cultural differences among different age groups and between boys and girls play roles in these demographic variations.

Finally, and very importantly, a depressed mood may represent psychiatric and medical disorders other than clinical depression. Bipolar disorder may be the cause of the depression, (read about bipolar disorder here) or a child may suffer from a traumatic-stress disorder, or an adjustment reaction to a difficult life event, such as the death of a family member (see our post that addresses that topic here). Also, a depressed mood is often a nonspecific aspect of an illness like thyroid disease, anemia and mononucleosis, or the result of nutritional depletion seen in conditions like anorexia.

How Do You Treat Depression?

Treatment for depression involves both therapy and medications. Many children with depression need talk therapy, in which the therapist helps the child understand and cope with his or her feelings. Family therapy and education are also helpful. Medications prescribed commonly include antidepressants, especially serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs). These medications lack the side effects of earlier antidepressant medicines and include agents such as fluoxetine (Prozac), paroxetine (Paxil), sertraline (Zoloft), fluvoxamine (Luvox) and citalopram (Celexa). Each of these is likely to be effective for depression, though many children may respond to one medicine over another due in part to the specific qualities of each medicine. In addition to the serotonin reuptake inhibitors, other effective medicines include bupropian (Wellbutrin) and venlafaxine (Effexor), among others. A combination of talk therapy and medication is often the most helpful treatment regimen.

Julia will get better. What we know about the treatment of child and adolescent depression has grown considerably even in the last two decades. She’ll need monitoring, and with any luck, she’ll connect with her doctors and other clinicians so that she feels comfortable calling them during times of crisis. In fact, sometimes just knowing what one is suffering from provides great comfort. She’ll likely be playing her bass again relatively soon.

Share

Share Tweet

Tweet