Anorexia Nervosa And Access To Care

Posted in: Podcast, Teenagers, Young Adults

Topics: Mental Illness + Psychiatric Disorders, Real Lives Real Stories

As we recognize National Eating Disorder Awareness Week here at The Clay Center, we hope the information we share will be both informative and useful. For even more information about eating disorders, and ways you can help make a difference in the life of a loved one or for yourself, please visit the National Eating Disorder Association website. Remember, “It’s time to talk about it.” #NEDAwareness

***

This blog post is part of a series entitled Real Lives, Real Stories: Personal Experiences With Mental Illness.

Note: The following person’s account of his/her personal experience has been published with his/her consent to support the mission of The Clay Center for Young Healthy Minds, and let others in similar situations not feel so alone.

Intro music written and performed by Dr. Gene Beresin.

Outro music arranged and performed by Dr. Gene Beresin.

People die from anorexia nervosa.

This is true of other psychiatric syndromes, but with anorexia, the cause of death couldn’t be more straightforward. People with anorexia literally expire from the complications of malnutrition; they starve and they die.

Your heart cannot beat if you don’t feed it. Your immune system can’t protect you without food. Your bones crumble, your kidneys fail, your liver sputters and your brain wanders, all as a result of inadequate food.

Suicide is common. Without proper nutrition, depression is prominent and thinking is blurred. Coping mechanisms falter. Life can seem unlivable.

Anorexia nervosa is an awful disease.

So, here’s the really strange thing about anorexia:

Despite the awful and potentially fatal outcomes that accompany this syndrome, despite the fact that anorexia has a death rate that is more than 12 times higher than any other psychiatric syndrome, third-party payers still try to balk at providing adequate coverage.

In 2008, the Federal Mental Health Parity and Addiction Equity Act put special restrictions on the coverage of the treatment of eating disorders. While the explanations for this exception vary—some have suggested that this is because eating disorders are thought to lack a biological basis—it’s clear that getting standard-of-care treatment for anorexia remains problematic even to this day.

In 2010, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the 9th Circuit in California found itself facing what was essentially a logic problem. The case of Harwick v. Blue Shield of California noted that while the insurer agreed that the residential treatment requested for a patient with anorexia was medically necessary—thus making it in compliance with existing parity statutes—coverage for residential treatment was not authorized because it was not part of the health plan. The court ruled in favor of the patient, but the fact that this even ended up in court is shameful. Can you imagine an insurer refusing to pay equally for the medically-necessary care of any other disease with such clear risks?

Thus, we have a disease for which good treatments exists, for which treatment is life-saving, and we still find patients fighting, literally, for their lives. It’s in this spirit that we’d like to share with Nicole’s story.

Nicole’s Story

Nicole is a remarkable 16-year-old teenager; she is academically and socially accomplished, and she speaks with wisdom that belies her age. Perhaps most striking, she has faced anorexia nervosa head-on, and can discuss her struggles with impressive humility and insight.

For example, we know that eating disorders are often chronic, frustrating and stubborn conditions. Still, Nicole appears to have navigated these treacherous waters with admirable strength and determination. What then, can we hope to learn from her story?

To begin with, we can acknowledge that her bout with anorexia has not been easy. She suffered significant depression, even suicidal ideation, as she muscled through the course of her illness. This aspect of her history is, perhaps, the most important take-home message: the work toward recovery from an eating disorder is never straightforward. Instead, each patient must find a unique way to work with his or her treatment team and family to progress toward good health. We can also note that anorexia is typically an insidious and very much unconscious development; as you’ll hear from Nicole in the podcast, the syndrome essentially snuck up on her and her family.

Still, Nicole is not unlike many girls who develop anorexia nervosa. Her temperament is typical—perfectionistic, compulsive, obsessive and competitive—and, in fact, just what we’d expect and perhaps even laud for its capacity to yield superior performance in both academic and extracurricular activities. However, combine that temperament with her love of dance, and one can begin to appreciate the “perfect storm” that is the source of this disease. Ballet dancers have little room for error, perhaps one of the worst of all being gaining too much weight. Nicole’s desire to be the very best dancer, combined with the potentially overemphasized mores of ballet culture, contributed to her insidious slide down the eating disorder path. Indeed, the development of the eating disorder itself can become a major source of guilt for girls like Nicole.

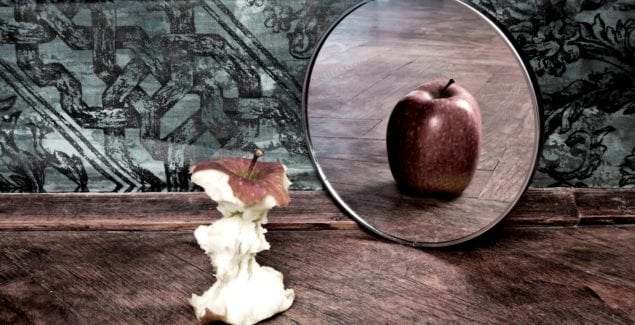

Now, add to this one of the most important psychological qualities that can predispose an individual to an eating disorder: children and adolescents who develop disordered eating are extraordinarily sensitive to relationships. They also couple this sensitivity with a deep concern for letting others down. These are, of course, generalizations, but for many patients, this is the Achilles heel of the syndrome. Nicole’s concern for approval from those she loves the most—parents, teachers and coaches—leaves her with painful feelings of disappointing others and herself. In essence, she enters a dangerous cycle that becomes a proverbial “lose-lose” situation. She becomes particularly adept at losing weight, and takes pride in her ability to do so. At the same time, she continues to “let down” her friends and family, causing her self-esteem to plummet. But now, however, she has a new source of self-esteem: withstanding hunger and losing weight. She thus replaces her former accomplishments with the sole accomplishment of weight loss.

This is where anorexia becomes particularly scary.

As Nicole progressively drops more and more weight, her friends, family and doctors become concerned. In response, Nicole becomes angry and frustrated. She feels that no one understands—not her parents, and certainly not her therapists.

Obviously this state of affairs cannot continue. Eventually, Nicole finds it impossible to keep up with dance, school and friends. She thinks most poignantly and often about food and body image, growing increasingly obsessed with becoming thinner and thinner. As Nicole can tell you now, her condition caused her to lose touch with the fun of being a teenager.

Eventually she suffers an injury from dancing that requires surgery. This final straw is what causes her to abandon hope altogether. She feels entirely alone, that no one can or will ever understand her. Ultimately, it’s this despair that leads to her suicide attempt.

So, what made the difference? What cracked the denial? What allowed Nicole to overcome the inability to work toward recovery?

Nicole is adamant about what made the difference. The critical importance of her relationship with Dr. Emily Gray, her psychiatrist and therapist, saved her life. For Nicole, faced with utter desperation and overwhelming guilt, she found in Dr. Gray someone whom she could trust. Dr. Gray, she felt, listened to and understood her.

With the foundation of this therapeutic relationship, Nicole had the support and courage to begin to see the patterns in her life that pushed her to the brink. She could focus more clearly on her fears and obstacles, as well as her strengths. And, most importantly, she felt capable of taking on the necessary challenges—starting with learning to advocate for herself. Naturally quiet and fearful of self-revelation, Nicole nevertheless enrolled in a public speaking class. She changed schools. She shared her needs with her family and friends, and was able to accept their care and support. And she learned, often painfully, that her perfectionism was making her sick. Through her work with Dr. Gray, Nicole found strength in the accomplishments that made her happy and healthy.

That’s an inspiring amount of insight for a teen as young as Nicole.

In summary, Nicole had a serious bout with a serious medical condition, and was lucky enough to encounter a talented and gifted physician who was able to help her recover. She was also lucky enough to be able to financially access the care she needed. Her story, therefore, is particularly compelling. Before she can began recovery, the course of her illness was emblematic of the suffering that thousands of young men and women with anorexia nervosa face every day. People with anorexia nervosa do, in fact, get better. But it takes time, effort and support.

Awareness and understanding will go a long way in getting these young people the help they need—and they deserve.

We wish to thank Nicole for her editorial suggestions and approval of this blog, and for her willingness to share her personal story.

A version of this post originally appeared and was written by the authors (Beresin, Schlozman and Gray) on WBUR’s CommonHealth.

Share

Share Tweet

Tweet