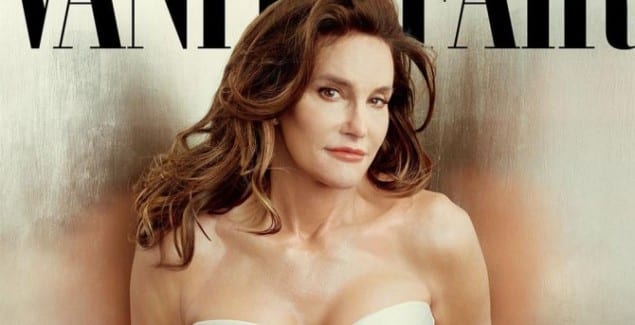

How Do I Talk To My Kids About Caitlyn Jenner?

Posted in: Hot Topics, You & Your Family

Topics: Hot Topics, LGBTQ+

“How do I talk to my kids about Caitlyn Jenner?”

I suppose this question is inevitable now. That’s not a bad thing, but it is a deceptively tricky inquiry. Perhaps unexpectedly, I’m finding it harder to hash out a well-rounded and developmentally-adjusted response to the issues of gender and identity as they pertain to transgendered individuals than answer the more typical questions that come my way. In other words, whereas I feel that I am in familiar territory when asked how we might discuss pertinent social and high-profile phenomena such as gay marriage or perhaps cheating among pro-athletes (both topics that we’ve addressed here at The Clay Center), the fact that transgendered individuals now appear on the covers of magazines in the supermarket has proven a harder topic to translate into discussable terms for parents and those who advise them.

So, rather than take a stab at what makes sense to say (and I WILL make some suggestions in this piece), let’s start by examining why this is a more difficult topic in the first place.

I know that gender is itself a tricky issue; after all, I was raised on Marlo Thomas’ Free to Be…You and Me, where Rosey Grier, the All-Pro defensive tackle for the Los Angeles Rams, told me that “It’s All Right to Cry.”

I also learned at a young age from “William’s Doll” that boys could be chided for loving dolls, and at the same time benefit from having them. My favorite skit from the entire album and TV broadcast is the two babies, voiced by Mel Brooks and Marlo Thomas herself, who each make up their minds about each other based on how they think their mistaken genders ought to behave—rather than how they truly feel.

In fact, Free to Be…You and Me isn’t a bad place to start this discussion. But, it still begs my initial question: if I can so easily address Free to Be…You and Me, and if that particular project was unabashedly about broadening expected gender roles, then why do I feel stymied when asked how we might talk with our children about the growing awareness of transgendered individuals?

In part, I think the answer rests in a number of assumptions that the false simplicity of a question like “How do I talk about…” engenders. Free to Be…You and Me was quite radical for its time, and is still controversial in some circles. Still, nowadays we have women and men in increasingly equal levels of responsibility. We have two women running for president right now; we have as many female doctors as men. I think it is therefore a mistake to conflate the “gender equality movement” with the “transgendered movement,” and that’s because it strikes me as a mistake to call the newly publicized transgendered movement a movement at all.

It’s not as if there weren’t transgendered individuals before. It’s not as if feeling uncomfortable and even intolerant of your chromosomal gender is new. What’s new here is the willingness to talk, or at least try to talk about these issues in the absence of judgment and criticism, and with a level of open-mindedness that often belies our somewhat stodgy impulses.

Also, recall that we have almost no research on this topic. Articles and studies do exist, but they are scarce when compared to other hot social topics. Often, when we lack anything beyond very rudimentary research to support our views, our brains naturally fall back on old assumptions and even prejudices.

And that, I’d argue, is where we can find common ground with other issues of the day and days past. A new issue, a provocative issue, makes its way onto the airwaves and into the newspapers. Even as we’re still forming our opinions and talking points as parents, doctors and educators, we’re then inundated with increasingly heated debates over the issue at hand. The airwaves do not pull for careful consideration; they pull for reactionary knee-jerks and corresponding counter-balances. We thus swing like pendulums from one extreme to the other, and yet, the best thing we can do for our children is teach them careful and empathic consideration. And, in doing so, let’s recall that we don’t have to entirely understand. In fact, we can’t understand; that’s the most important part.

So, if I’m asked how we can respond to our children about transgendered individuals, I’m going to answer as I would for almost any inquiry that probes a controversial, provocative and potentially titillating topic: I’m going to begin with turning the tables.

- Ask your child what he or she thinks first before you answer. You’d be surprised how many times kids will take what to an uptight adults feels potentially confusing as not a big deal. It’s not really in our children’s best interest to get riled up. So, if they’re not bothered, don’t unnecessarily turn this into something bigger than it has to be.

- What if your child asks, “Why would Caitlyn Jenner do what she did?” or even, “Why are we calling someone who used to be boy a girl?” Three words seem to me to make sense here, at least at first: “I don’t know.” We can’t know what Caitlyn was thinking other than she wanted to be and feels at home as a woman. We can’t feel what she feels, but not because she’s somehow strange or different; we can’t feel what ANYONE feels. That’s the nature of being human.

- Finally, what if your child asks, “Why is this such a big deal?” For this one, and this is the question I’m hearing most commonly, I’d begin by making sure you understand what constitutes a “big deal” by your kid’s standards. Is it a big deal because it’s all over the media? Is it a big deal because your child wonders about gender roles? Is it a big deal because your child is bothered by the news?

Here’s where you can remind your child that it’s a big deal in part because the circularity of media makes it such. It’s a big deal because gender identity itself is in flux throughout development. To see someone entirely switch to another gender is not news because it’s foreign; it’s news because it is the understandable evolution of our own developmentally-natural gender identity fluctuations. The biggest mistake we can make when addressing these issues with our kids is to make them feel as if they are not free to explore these differing roles and ideas.

I’m aware that I’m steering clear here of the hotter social issues. I’m aware that there will be some who fundamentally disagree that a transgendered state is normal, and that there are others who will equally espouse the need that we are entirely accepting. I’m hoping that this blog can appease both sides. We know that children and teens do best when they are cool-headed and thoughtful. A fervency of opinion that is thrust upon them does them no good, and parents are likely to see that their children, especially the older ones, will express contrary notions to these fervent opinions simply as a function of the desire to individuate. This goes for both sides of the issue.

Gender is a funky thing. It’s nuance masquerading as absolute. It’s identity either staring down or siding with biology. It’s a hodgepodge of cultural expectations and biological determinants, and we’d do well to remember that it is therefore complex and not at all simple.

When your child asks you what you make of Caitlyn Jenner, I’d argue that we can’t make anything of Caitlyn Jenner, because we can’t possibly know what Caitlyn thinks or feels other than what is captured in public commentary. But, I’d make sure that we are empathic in both tone and language, and if more questions come, I’d leave the door open for more complicated thinking. Let’s let the dust settle as our kids work this out for themselves. Our job as parents and as advisors to parents is to advocate for careful consideration. To this end, we can discuss this issue as we would any issue that has provocatively captured the public’s whimsy—we can model calmness in the maelstrom of media frenzy, and in doing so, set the stage for the next social issue that comes our way.

Share

Share Tweet

Tweet