Talking to Your Children About Asian Hate

Posted in: Parenting Concerns, You & Your Family

Topics: Bullying, Hot Topics

Read and share this article in Chinese. Thanks to MGH Marketing for making this possible.

Over the last year, there have been very disturbing reports and videos of hate and violence towards the Asian community. As a Chinese American, these events have left me with a sense of increased vulnerability for myself, my family, and my community. It can be natural to want to shield our children from these incidents, but we can also use these awful acts of violence and racism to increase awareness and open a dialog with our children.

Historical Context

While there may be a greater awareness of racism towards the Asian population recently, there unfortunately is a long history of racism towards the people of Asian descent in this country. The Chinese Exclusion Act in 1882, which banned people from China from entering the country and made Chinese people unable to become US citizens, and the forced internment during World War II of people of Japanese descent, many of whom were American citizens, are two very notable examples by the US government. During the current pandemic, references to COVID-19 as the “Kung-Flu” were purposely used to stoke division and contributed to racism towards the Asian community.

Starting a Conversation With Children

Understandably, parents may feel reluctant or anxious about starting a conversation about racism or acts of hate towards Asians. It’s okay to feel unsure about what to say. In some cases, children themselves might bring up the topic by repeating what they’ve heard or seen. In other cases, it can be a deliberate decision on the part of a parent to start a conversation.

Why This Is Happening

Children may have questions about why acts of violence or hate are being directed towards Asians. They might have their own ideas, and asking them what they think or what they’ve heard can be a great conversation starter. It can also be helpful to reflect on the past year and brainstorm ways their own lives have changed during the pandemic. Perhaps they were no longer able see friends or hug their grandparents the way they used to. They might have needed to participate in online school or adjust to wearing masks.

Exploring those shifts to their lives and how those changes made them feel can lead to a larger conversation about how when things change, some people, including adults, sometimes feel upset and try to blame someone else. Because the first reported cases of COVID-19 were reported from China, some people directed their anger at Chinese people and other Asians. It’s important to talk about how it’s okay to feel frustrated or angry about the coronavirus and at the changes in life caused by the pandemic, but that it’s unfair and wrong to blame or attack people.

Anger about the pandemic can be one of the recent reasons for violence and hate directed towards Asians, but unfortunately, as noted above, there is a history of racism towards Asians even prior to COVID-19. It can be helpful to discuss other examples of prejudice and racism. School-aged children, for example, may already know about the civil rights movement and the discrimination that Blacks in the country faced and continue to face. Talking about these issues can bring greater awareness of other people’s experiences and reinforce the need to treat all people with dignity and respect.

How Much to Disclose

As a parent, you should choose what you feel comfortable sharing with your child, depending on their age, developmental stage, and sensitivity. A conversation alone can bring up many questions about what happened, why it happened, who was involved, and the outcome. Be honest and direct with your answers, but there is no need to over-share details. By gauging your children’s reactions, you can decide where the discussion leads next. Take cues from your children in deciding whether to continue a conversation or not. For young children, a single conversation alone is often enough.

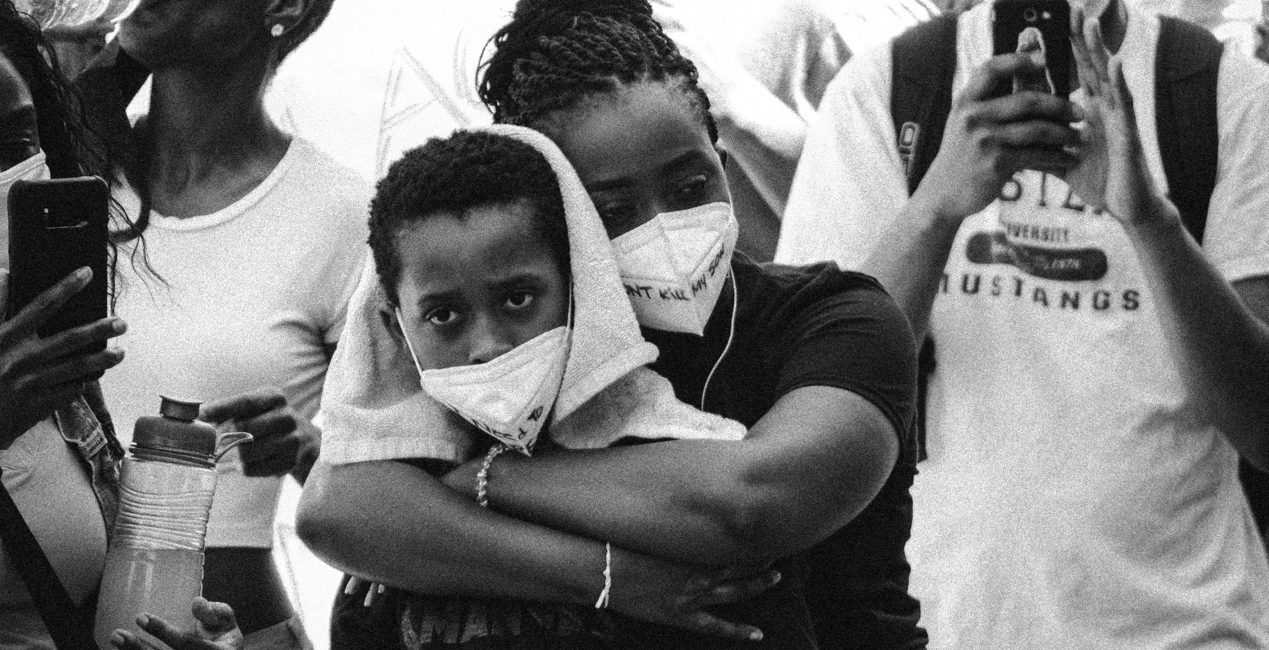

For children who are a little older, you may choose to share a carefully chosen image or video of violence or racism. Know your children. For some children, videos and images may be too emotionally unsettling and would not be recommended. If you do decide to share, remember that less is more; sharing too many images can be overwhelming. Be very selective of what you introduce, and consider how your child might react before you show it. Pre-screen what they are about to view and be prepared to discuss what they see ahead of time. It is essential to put the image or video into context for the children and tell them what they are about to see. It can be very helpful to narrate and explain what they’re seeing as they are watching and to help them process the experience afterwards. Asking them about the primary people involved, the bystanders, what happened, and why it was wrong can foster communication. You can also explore what possible emotions the victim, attacker, and potential bystanders may have had.

It’s also important to check in with your children about how the image or video made them feel. Children may have a sense of increased vulnerability or fear about something happening to themselves or someone they care about. Reassure your children about the steps you and your family are taking to stay safe. Be clear that you are available and open to talking about their experiences and that if anything happens to them, to tell you or a trusted adult.

Witnessing or Experiencing Racism Towards Asians

It is my hope that children will never be exposed to the severe violence or aggression towards Asians that has made national news. But also let your child know that racism towards Asians can take many forms. It can be as obvious as someone making a racial slur, but it also can include things like people making unkind remarks about someone’s skin tone, making fun of the shape of someone’s eyes, or mocking how an Asian language is spoken. Less obvious forms of racism can include making assumptions that they are more passive or weak because they are Asian. If you are a parent who experienced racist comments or actions, it’s okay to disclose to your children how those words and actions made you feel. It is essential to let children know that they are not at fault if someone directs racist actions or words towards them.

Giving Kids Tools

If your children experience or witness Asian-related hate or racism, it’s important to give them options.

- Stress that their safety is essential and that you would never want them to put themselves in harm’s way.

- If they feel safe, they can choose to speak up for themselves or for others. Role-playing can sometimes be helpful.

- Let them know that it’s also okay to not engage and to instead find a trusted adult, such as a teacher or parent, and tell them what happened.

- Some children may be also be interested in activism, such as organizing opportunities to create greater awareness in their school community or making signs and attending rallies against Asian hate in their town.

- A grounded and positive sense of self can help provide a strong foundation for children who may experience racist remarks or activities. Exposure to books and movies that promote positive images of Asians can help to foster pride in their heritage and to promote a positive sense of identity.

Looking Towards the Future

While the year has brought about some horrific acts of violence and racism towards members of the Asian community, there is hope for the future. There is already more awareness and dialog about these issues. A single conversation with a child today can lead to continued conversations as they grow and mature. These ongoing discussions can also help build empathy towards other groups who might also experience discrimination or acts of violence, and slowly make for a brighter future.

Share

Share Tweet

Tweet