How Do I Know If My Child Needs Testing?

Posted in: Grade School, Infants & Toddlers, Pre-School, Teenagers, You & Your Family

Topics: Child + Adolescent Development, Learning + Attention Issues

Jim’s mom was frantic when she called me. Jim had been having difficulty in school since the end of kindergarten, at which point it was clear he still didn’t recognize all the letters of the alphabet. He continued to struggle in first and second grade, getting some extra help from the reading specialist. When Jim’s mom and I spoke, she had just come from his third grade parent-teacher conference, where his teacher suggested he get “tested” because she was concerned about his reading and writing skills. While this suggestion didn’t exactly come as a surprise to Jim’s mom, she was still upset by the suggestion itself. She was scared an evaluation might be used to “label” Jim, and that he’d forever be known as the “kid who couldn’t read.”

Alexandria’s parents were similarly confused as to how an evaluation might help their 4-year-old who was now struggling with social relationships in preschool. Both Alexandria’s teacher and pediatrician suggested that an evaluation might be useful in understanding why she seemed to lack an interest in playing with other children. Her parents wondered how a testing evaluation could be helpful, and weren’t sure what the process entailed.

Both Alexandria and Jim were referred for a testing evaluation, a comprehensive evaluation that can be used to diagnose a certain problem (such as a learning disability), to clarify what is wrong (is it ADHD or depression?), and/or to provide strategies for school and home. Each type of testing evaluation requires a fully trained, specialized professional. The professional will take a full history of your child and the problems he is having, and then use clinical observations and a combination of tests to gather a wealth of information about your child and his functioning. The evaluator compares your child’s behavior, test scores and history with those of same-age peers to figure out if the child is substantially stronger or weaker in any given area. Usually some type of diagnosis, or formal label, is given to account for the concerns that brought you to the evaluation in the first place. The terminology used for types of evaluations can vary, but the most common ones include the following:

- Neuropsychological Evaluations: A test battery designed to measure a child’s cognitive skills and brain functioning in areas such as intelligence, attention, memory, learning and visual perceptual skills. It is the most comprehensive of the test batteries that are mentioned here, and is typically administered by a licensed clinical psychologist.

- Educational/Achievement Evaluations: A test battery specifically for measuring a child’s academic skills in decoding, reading comprehension, spelling, math and writing. This type of testing battery is usually administered by a licensed clinical psychologist or school psychologist.

- Psychological Evaluations: A test battery for assessing a child’s emotional, social and behavioral functioning and personality traits, usually administered by a psychologist.

- Developmental Evaluations: A test battery usually administered in children under the age of 5 years that gives information about a young child’s level of development in language skills, motor skills, cognitive skills and social skills. These types of test batteries can be administered by a developmental pediatrician, psychologist, or a team of professionals who have expertise in specific areas of development, such as language or motor skills.

- Other Types of Evaluations: Include Occupational Therapy Evaluations (that evaluate a child’s fine motor and sensory-motor functions), Physical Therapy Evaluations (that evaluate a child’s gross motor skills) and Speech/Language Evaluations.

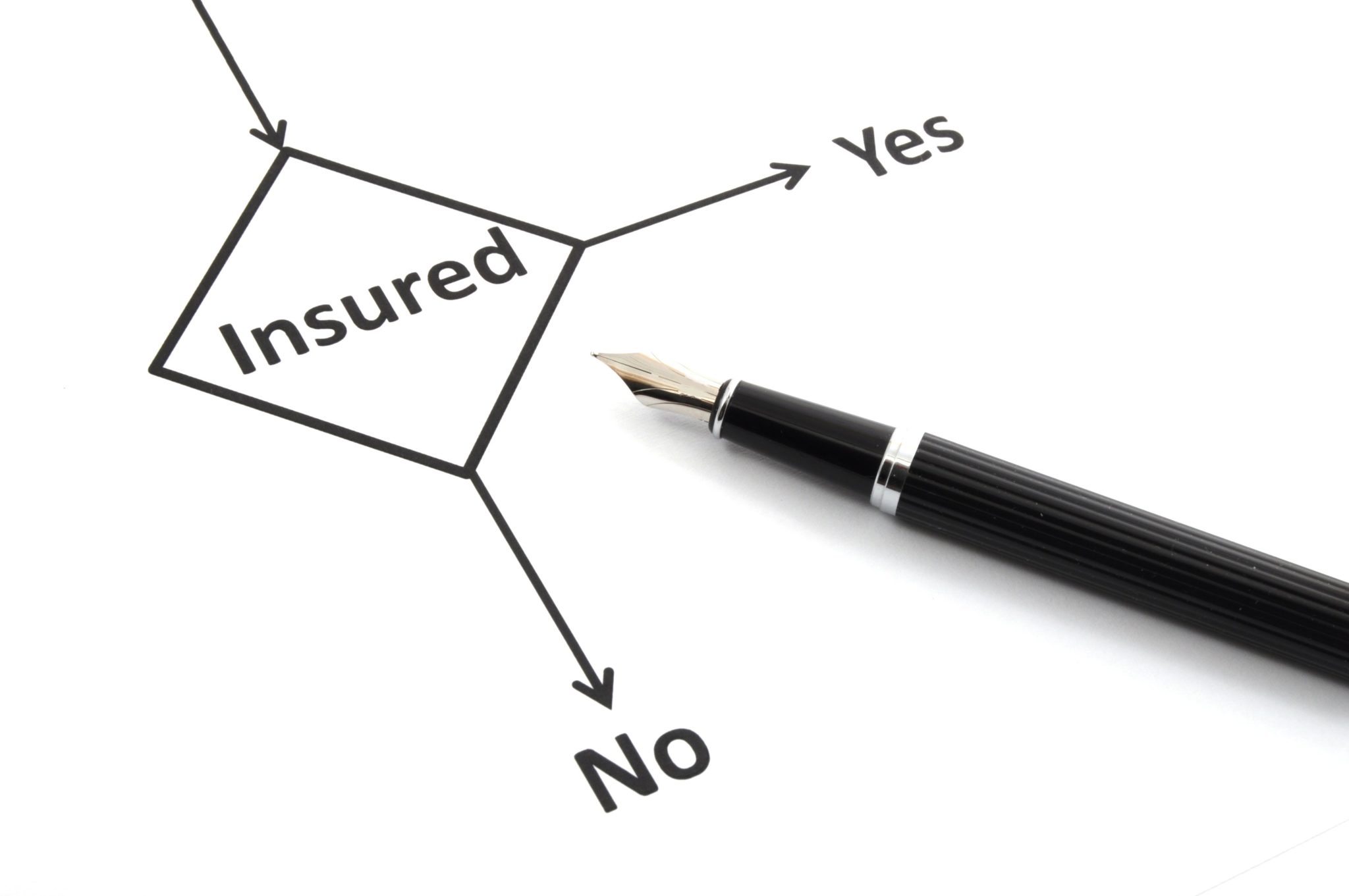

So when can a testing evaluation help? Testing is most often used to help provide an explanation for a problem your child has. Testing is not always necessary for understanding what is wrong, but in many cases it proves essential for an accurate diagnosis and an appropriate treatment plan. Difficulty with writing, for example, could be attributable to a number of problems, such as fine-motor weaknesses, visual-motor integration delays, problems generating ideas, difficulty organizing one’s thoughts, or inattention. Without the right kind of testing, you won’t necessarily know the cause of the problem, nor will you know the type of interventions necessary to improve it. Even if a child has already been diagnosed with a certain disorder, such as dyslexia or an autism spectrum disorder, the results of a good testing evaluation will almost always yield more specific information that can enhance the potential for a prescribed treatment to help your child. When a child has a constellation of problems, a testing evaluation can shed light on the relative severity and possible connections among them, helping to reveal any co-occurring disorders (such as the presence of a learning disability in a child who has already been diagnosed with ADHD), or assisting a practitioner in determining which problems should be addressed in treatment. It can also be helpful in highlighting cognitive and emotional strengths that can further augment or guide interventions.

Though I might be biased—I’ve seen so many examples of how testing can assist in diagnosis and treatment of children—I believe that testing evaluations are useful in assessing and understanding the majority of the concerns described below. This is hardly an exhaustive list, but if you’re concerned, check them over and consult with your child’s teacher, pediatrician, or other professional about any that apply to your child. You are right to be concerned if you have noticed the following:

Language and Speech Skills:

Infant/Toddler:

- Has trouble sucking or swallowing

- Isn’t babbling by around 10 months

- Isn’t using single words by age 15-18 months

- Is using only one or two words at a time by age 3 years

- Is not understandable to others outside the family by age 3 years

- Doesn’t seem to understand what you are saying by age 2½ years

- Repeats what is heard from others, from TV and so forth, rather than responding

Preschool:

- Words come out jumbled or in poor order by age 4 years

- Has difficulty answering questions such as “what?” and “when?” and “where?” at age 4 years

- Can’t articulate (make sounds accurately) clearly by age 5 years

- Gives only brief responses to open-ended questions by age 4 years

School-Age and Up:

- Seems frustrated by difficulty finding words or communicating

- Has trouble getting the gist of jokes or idioms such as “You’re pulling my leg!” by age 6 years

- Has a continually scratchy, rough, nasal, or squeaky voice

Motor Skills:

Infant/Toddler:

- Does not attempt to reach for objects by 3 to 6 months

- Cannot hold head upright by 4 months

- Is not sitting up by 10 months

- Cannot use a pincer grasp (thumb and forefinger to pick up small objects) by age 1 year

- Is not walking by age 18 months

- Isn’t going up stairs by age 2½ years

- Has problems with balance at any age over 2 years

- Walks or runs awkwardly at any age over 3 years

Preschool/School-Age and Up:

- Doesn’t alternate feet on the stairs by age 4 years

- Has excessive difficulty writing her name or can’t write it legibly by age 5 years

- Writes letters or numbers illegibly at age 5 to 6 years

- Isn’t riding a tricycle or bike with training wheels by age 5 years

- Has weak muscle tone or low stamina at any age

- Has difficulty with playing sports (e.g., kicking the ball, catching)

Social Skills:

Toddler and Up:

- Has problems making and keeping eye contact with your or others

- Has problems figuring out how to join in with other kids

- Tends to miss or misunderstand what is meant by others’ behavior (often called “problems reading social cues”)

- Has difficulty carrying on the natural rhythms of conversation or play

- Shows a lack of social responsiveness to you or others (e.g., does not respond when her name is called; does not acknowledge a child who comes into the room)

- Does not engage in pretend play by age 3 to 4 years

Learning:

Preschool and Up:

- Has problems with rhyming and learning letters and their sounds by age 6 years

- Has memory and organization problems

- Has difficulty paying attention or following directions

- Experiences frustration doing grade-level work at any age

- Has gaps in skills or inconsistent grades

- Experiences a decline in grades or school performance

- Has consistent problems getting homework done

- Routinely runs out of time on tests

- Tells you he hates school or refuses to go

Behavior:

Preschool and Up:

- Has frequent explosive tantrums beyond age 3 years

- Insists on having things a certain way or strictly following a routine

- Uses fantasy play excessively or daydreams

- Loses interest in friends or activities

- Suffers self-inflicted cuts, usually on arms and legs

- Chooses friends who are “high risk” (e.g., may smoke, break the law, do drugs)

- Has odd ideas or preoccupations

- Plays with fire or sets fires

- Demonstrates frequent sexualized play or talk

- Verbalizes a wish to die or kill himself

- Exhibits overly aggressive or destructive behavior

As you might has guessed from reading this long but hardly complete list, there is great variability in the kinds of problems described, as well as their root causes—which can range from an attention problem, to a learning disability, to a developmental disorder, to an emotional issue such as depression or anxiety. Regardless of the problem, testing can tell your child’s general developmental level in language, motor, social, behavioral and emotional functioning. Testing can provide an estimate of your child’s innate ability, often referred to as intelligence level, and assess her cognitive strengths and weaknesses. A comprehensive evaluation with the right evaluator should give you information about your child’s academic skills too, such as the grade level of his reading, or where she is relative to her peers in math or writing. Testing may also give you information about your child’s various processing skills—how she takes in information from the world through her different senses, and how she is able to use that information. For the purposes of making diagnoses, documenting the need for therapies or services, and figuring out the potential basis of an emotional or behavioral problem, testing evaluations are typically essential.

When is testing not useful? There are certainly some questions that a testing evaluation can’t answer. For example, no evaluation, even with the most experienced clinician, should predict your child’s future long-term functioning. I have worked with families who were told by professionals that their children would never talk or learn to read—and they were wrong. No professional is capable of knowing the full potential of another person, or the extent to which that person may benefit from interventions. These evaluations can give you a sense of what your child’s current limitations may be, and may estimate what kinds of problems your child could encounter down the road. However, the main purpose of a testing evaluation is to come up with solutions to the problems by recommending the right kinds of supports and interventions.

Share

Share Tweet

Tweet