What Do I Do If My Child Is Bullied?

Posted in: Grade School, Teenagers

Topics: Bullying

Este artículo está disponible en español.

Here’s a weird fact.

Until about six or seven years ago, the term “bullying” was pretty much absent from everyday use. In fact, six or seven years ago, if you had asked someone to define “bullying,” they’d probably tell you that the word itself was both old and old-fashioned. It conjured memories of rough and tumble playgrounds, of kids getting their lunch money stolen, of someone perhaps being taunted because of his girth or his braces.

Not anymore, however. Ever since a series of very high profile events, many of them involving the Internet, (and some even resulting in death by suicide of the person being bullied), the term “bullying” has been emblazoned in our lexicon.

Kids come home from school and talk about anti-bullying programs in the classroom. Local and national news routinely talk of ongoing bullying in urban, suburban and rural settings. Teaching curricula stress how to recognize circumstances that predict bullying behavior. And kids are presenting to their doctors with emotional and physical complaints that seem to tie directly to being bullied.

Is this an epidemic? Is bullying a new phenomenon?

Well, yes and no. To answer this question, we need to first define the term. How do we conceptualize “bullying”?

What exactly is “a bully?” It turns out that experts in sociology, pediatrics, education and psychology offer a variety of somewhat similar definitions. In general, all of these descriptions are rooted around the notion of a clear power differential in which a more powerful person mistreats and takes advantage of a less powerful person.

This, of course, opens the issue of bullying to settings outside of the classroom and schoolyard. Sports teams, after-school activities, and even places of employment are subject to bullying behavior. Importantly, experts avoid defining bullying as the simple presence of a differential in power. There will always be a boss at work. There will always be stronger kids, more “popular kids,” and smarter kids. When these individuals exercise their relative advantage malignantly and sadistically over other individuals, then bullying is said to occur.

Let’s look at a hypothetical scenario similar to some more recent tragic recent examples:

Rob, a 13-year-old boy, arrived at his new middle school in late December of his seventh grade year. As Rob’s mother was a career officer in the army, Rob’s family moved often. However, this was his first move as a middle school student. In other words, the normal developmental drives for acceptance and conformity were most powerfully felt by Rob exactly when he arrived at his new school.

Rob sensed this dynamic, and he struggled to fit into a new system. As a means of letting others know something about himself, he embraced his identity as an army kid. He wore army jackets and boots to his otherwise preppy school. He spoke with the southern drawl of his parents, though he was now in a school in suburban Sacramento. He proudly told everyone he met that his mother had already been deployed three times to conflicts overseas.

However, Rob wasn’t a very good athlete, and he was often a mediocre student. As his stories grew more tiresome to the other students, a group of boys started to mock him on Facebook. One of the students sent Rob a faux “friend request,” and Rob misinterpreted the gesture as a genuine sign of goodwill. He eagerly responded about how happy he was “to have found a friend who was different from the other jerks at this school,” and his response was subsequently shared with most of the student body.

The online heckling continued, and soon translated into a mixture of isolation at school that was occasionally interrupted by name-calling and even physical altercations. Rob complained to the guidance counselor, but did not tell his parents; he was, in fact, embarrassed that he was having such a hard time fitting in. The school did not take action, telling Rob that it was best to ignore the other kids. However, the bullying continued, and on a rainy Saturday afternoon, Rob tried to hang himself in his bedroom. His father discovered him before any real damage was done, and Rob was psychiatrically hospitalized. The psychiatrist who saw him thought that he was perhaps depressed, but all Rob could note was the maltreatment from the other kids.

So—is this truly bullying?

Yes.

There’s a clear power differential brought about by Rob’s standing as a cultural outsider, and a newcomer at school. Though there is not a single bully, the bulliers egged each other on, and Rob clearly did not welcome the taunting. One might be tempted to argue that Rob ought not to have called the other students “jerks,” but that’s a different topic than whether the way he was treated was deserved. Nothing anyone could do would make it OK for Rob to endure the near constant harassment he suffered.

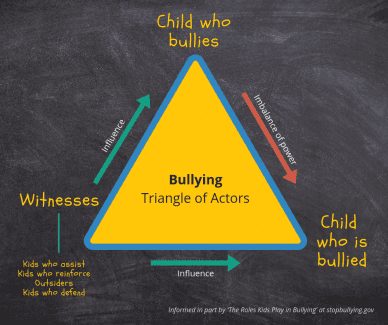

Studies of bullying scenarios note a triangle of actors: There are bullies, the those who are bullied and bystanders. Further analyses have identified that the bystanders subtly direct the bully’s attention away from themselves; for this reason, they have been called the “puppet masters,” doing all that they can to perpetuate the status quo in order to avoid harm’s way.

This model suggests a way to approach bullying in schools — no one at the school should be left out of the discussion:

- The kids who made fun of Rob can be helped to understand that Rob’s behavior did not give them abject permission to abuse him.

- Rob can be helped to acknowledge that calling the other students “jerks” made it even more difficult for him to fit in.

- The kids who were, in fact, aware of the situation can be challenged as to why they did not intervene.

In schools where this kind of approach has been employed (often using role-playing and lengthy discussions), the incidence of bullying has dramatically decreased.

But what about Rob? Is he depressed? Not necessarily.

Nine out of 10 kids who make serious attempts on their own lives do suffer from a severe psychiatric syndrome, and depression is the most common among these. But, one in 10 of these kids suffer severe social disappointments like Rob’s. These kids do not necessarily have a formal psychiatric syndrome. The only way his parents can know about Rob’s suffering, is to ask Rob and his teachers how he’s doing. The teachers themselves need to be trained to watch for situations like Rob’s, and many schools have now instituted special teacher trainings to address these difficult issues.

Parents:

- Ask your child if other kids are treating him or her well.

- Ask the teachers.

- Watch how your child interacts with his peers.

- Be aware as much as possible as to whether harassment exists in social networking sites.

Finally, although Rob might not meet criteria for depression, he certainly could use some help. Thoughtful listening by his parents, a chance to start over with the kids at school, and a counselor skilled in working with adolescents are absolutely necessary for Rob to adequately process what has happened, and move forward. Similarly, interventions in the school will also help to prevent future episodes of bullying behavior.

Share

Share Tweet

Tweet